In the modern day, there are a number of software options for artists who wish to animate their illustrations without a lot of the tedious work that might otherwise be involved in the process. One company that produces this kind of software is Live2D, whose products focus on dynamic and configurable 2D models of illustrations. Cubism is their flagship product at the moment, boasting many of the tools that a regular 3D modeling program might possess. Recently, Live2D announced the development of a new software program: Euclid.

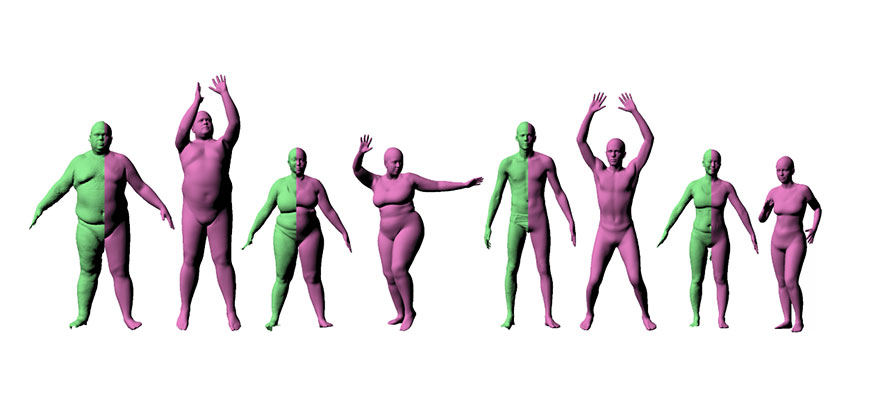

Euclid is intended to be the next-generation replacement for Cubism, and is notable because Live2D asserts that the software can render a 2D illustration from any orientation — that is, in an "orbit" around a given illustration. Cubism, by comparison, can only render such illustrations from a maximum of 40 degrees to the left and right, if one is generous enough with their definition of the illustration. A prototype of the new and unreleased product has been shown, with a demonstrator making use of the Oculus Rift to view a particular rendering of an illustration from various angles. So far, it’s impressive: all of the animated features seem to retain their definition, regardless of the orientation they’re viewed at. That is, of course, the goal of Euclid.

An emphasis has been placed on more natural rendering of difficult characteristics, such as hair and other facial features. This is achieved mostly by means of layering in 3D space, to preserve the illusion of two-dimensional viewing. In addition, one may combine multiple illustrations to enhance the effect. Selective use of features contained within the product is also possible: traditional 3D modeling techniques may be applied to some parts of a character design, while Live2D animation may be applied to others. An example was given of a character that had its main body modeled normally, while the head and facial features were given the Live2D treatment.

Considering that Cubism already contains a separate SDK for game developers, it is possible that an extension will also exist for the new product, so as to take advantage of existing architecture. In a recent press release, it was noted that Live2D Euclid technologies can be rendered in real-time within a 3D environment, allowing them to be manipulated by game engines as well as computer graphics applications. Oculus has already been demonstrated as a potential candidate for this approach, which would mean the two concepts could be combined to create a more immersive game (or CG movie) world.

Although competing technologies exist, the software Live2D has come up with is compelling. Only time will tell its full capabilities.