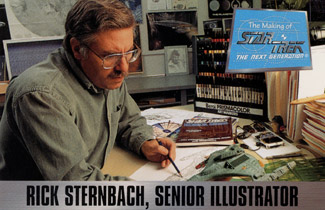

Not many people can say that they've taught Scotty how to fly a spaceship. Or shown Captain Picard the basics of using a Macintosh computer. In fact, Rick Sternbach is the only person I know who can.

Who is Rick Sternbach, you might ask? Well, if you've ever watched the USS Voyager glide out of a stellar nebula, or marveled at the delicate architecture of Deep Space Nine, you're already familiar with his work.

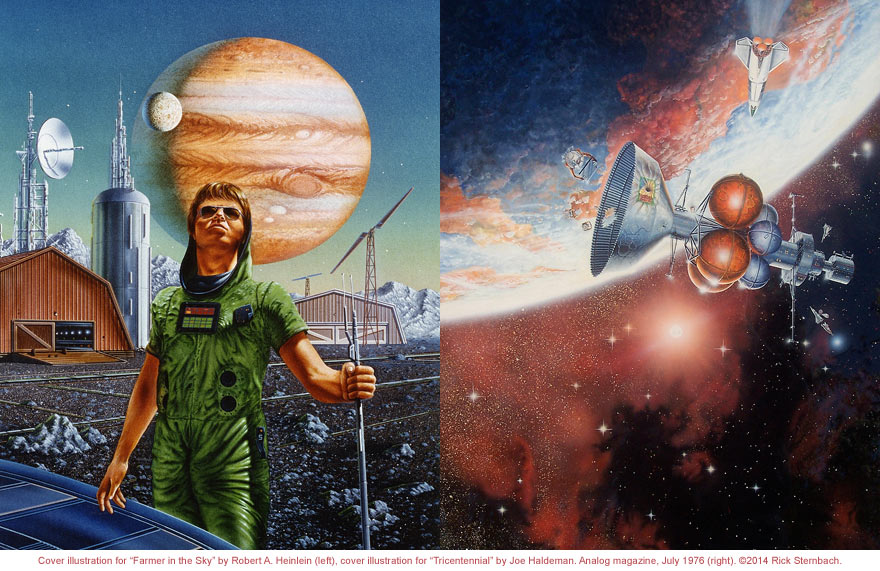

A seasoned designer and illustrator, Rick Sternbach has been bringing space to life since the early '70s. His illustrations, panel displays and prop and vehicle designs can be seen in numerous works of science fiction, notably: "Star Trek: The Motion Picture," "The Last Starfighter," "Solaris," "Star Trek: The Next Generation," "Star Trek: Deep Space Nine" and "Star Trek: Voyager."

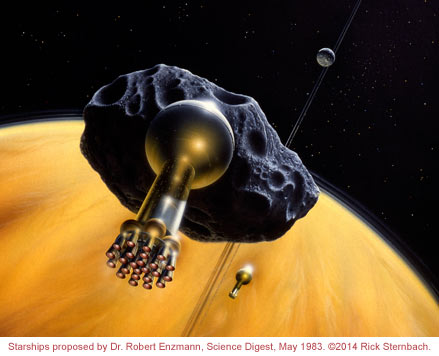

A founding member of the International Association of Astronomical Artists (formed in 1981), Sternbach has also created illustrations for scientific magazines and research institutions. His clients include some of the biggest names in science: NASA, Smithsonian, Sky and Telescope magazine and The Planetary Society. He even worked as an illustrator and special visual effects designer for Carl Sagan's "Cosmos" in the late '70s. At a time when planetary exploration was in its infancy, Sternbach's imagination soared beyond the limits of our technology — producing vibrant illustrations of a universe most had only glimpsed as pinpoints in the night sky.

We managed to pull Rick aside for a few minutes to talk about his work, along with three of his favorite topics: space, technology and science fiction.

You were an early adopter of computer graphics technology. What sparked your interest in digital art and design?

"Drawing, painting and designing things were major parts of my childhood and teen years. My dad was an architect and got me started early with machines of all sorts: trains, airplanes, boats, military vehicles… you name it.

"I’ve kept up with news of every technology — from developing new materials, to computers in design and drafting, to robotic assembly and control of systems. I’m as much a fan of CNC and RP as I am of CAD and CGI. Not all of these methods have entered into my daily work simultaneously, but I find it amazingly helpful to at least know what’s available and how they work, and know which will help achieve a particular result."

What was the first computer graphic you ever made?

"In the early 1970s, when I began doing illustrations for science fiction books and magazines, I was fortunate enough to meet up with a number of scientists, engineers, and science fiction writers. I regularly hung out with friends in the Boston area, some of whom were going to MIT. I had previously met Dr. Marvin Minsky in 1972, and through him or a computer science student, I made a square box on a cathode ray tube using a computer running Logo.

"Not much of a graphic, but that first experience led to all sorts of ASCII, dot matrix and plotter art back in the day. I had never taken any real computer classes, but absorbed as much as I could about the machines and displays and output devices. I had — and still have — a lot of very smart friends who helped out."

To what do you attribute your interest in space and space exploration?

"I grew up in the 1950s, a time when the means to explore space were just being developed. Through picture books, movies and plastic models, I was hooked. Exactly how we got into space as a civilization has continually fascinated me. I was around during a time when there was nothing made by humans in Earth orbit. We hadn’t yet sent any early probes crashing into the moon. Step by step, I saw it all."

How did you get involved with Star Trek?

"I had always been a big fan of science fiction films and television shows, so titles like "Destination Moon," "Forbidden Planet," "2001: A Space Odyssey," and "Star Trek" are permanently burned into numerous brain cells.

"Prior to the release of "Star Wars," when no one really knew what "Star Wars" was, I had seen a display of Ralph McQuarrie’s artwork for the film at the World Science Fiction Convention in Kansas City. The crazy notion hit me to see if I could migrate from Connecticut to Los Angeles to do prop and vehicle designs for the film industry. It actually took another year to do a scouting trip, but with portfolio in hand, I met with a number of art directors — including Joe Jennings at Paramount, who eventually hired me to work on "Star Trek: The Motion Picture."

What was it like to see your work on the big screen for the first time?

"I’d say it was pretty similar to seeing a first book or magazine cover in print. The first mass media appearance of a piece of art or a design is always gratifying; a nice ego boost, to be sure. It’s a definite validation that something seemingly created out of thin air, especially in science fiction, can be part of a bigger project.

"During the craziness of production, artwork gets done, gets sent off for approval, and the various other crafts do what they do with it. We sometimes don’t have a chance to see our work until we catch the dailies or an episode airs or a film debuts, but it’s very cool to see the final products. And as you know… we still talk about them years later."

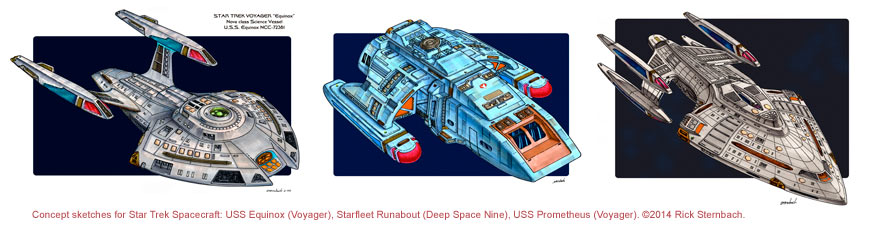

You designed at least a dozen of the now-legendary spacecraft in the Star Trek universe (USS Voyager, Deep Space Nine, the Delta Flyer). What's your process for concocting such detailed, believable ship designs?

"With an entertainment franchise like Star Trek, for me it’s a matter of blending engineering plausibility with the “coolness” factor — very much like what goes into automotive styling over a practical framework.

"We were fortunate that Star Trek was solidly anchored in the real space exploration of the 1960s, and I tried to carry that through the other shows. Of course, we have no such “super science” things as warp drive or matter transporters, but the point was to work with science and technology so that they could be extrapolated into 23rd and 24th century concepts that the audience could accept.

"A lot of the ship designs followed a lineage established by designer — and pilot — Walter M. Jefferies from the original series, and I and my fellow artists have evolved those ships, sometimes creating complete logical deck plans and routing maps for utilities conduits and computer cores. Viewers may not see everything that goes into a design — but the hope is that on some level, the designs and how the ships and props function will get them thinking, and give them some lasting idea about what might be possible. After all the neat crashes and explosions."

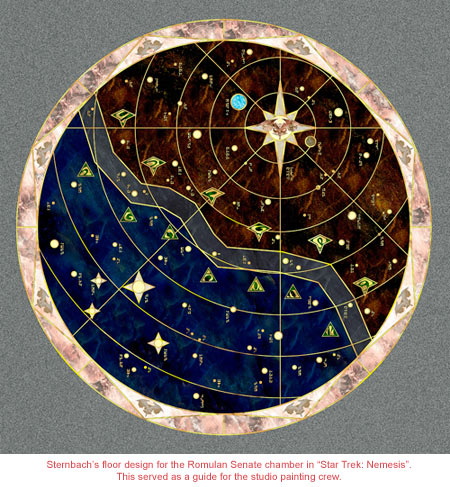

Helping to shape the Star Trek universe must have been a singular experience. Do you have any behind-the-scenes stories you can share?

"Let’s see…on "Star Trek: The Motion Picture," director Robert Wise held up filming, waiting for me to get to stage to tell Jimmy Doohan (Engineer Montgomery Scott) which controls to activate in the Starfleet travel pod. (I had designed the touch displays in the pod).

"Another fun time was seeing Professor Stephen Hawking on stage, playing poker on "Star Trek: The Next Generation" with Data, Albert Einstein and Sir Isaac Newton… and using a robotic arm that I designed.

"Also… in the very early days of working with our Macintosh computers, Patrick Stewart used to visit the art department and ask Mike Okuda and myself techy questions about his own machine. He once wondered, 'I know Command-X makes a bit of text disappear… and I know you can bring it back, but where does it go? It’s very disconcerting.'

You've created visual effects and illustrations for science magazines and research institutions. How do those experiences differ from designing spaceships and props for fictional TV series and films?

"I firmly believe that all astronomical art and space hardware design benefits from a good working knowledge of the material, whether its final use is destined for a science journal or a science fiction show.

"With the real space subjects, it’s good to know something about a lot of different areas. This can get pretty daunting; my space artist colleagues and I have discussed the fact that not only do we need to know how to draw and paint (and sometimes do CG renders), but we have to ask the right questions about planetary vulcanism, cratering densities, stellar formation, asteroid collisions, orbital resonances, and so on, to be able to provide as accurate a visualization as possible.

"The hardware subjects require just as much study; not many people outside of the actual engineering teams make a habit of learning about reaction control thrusters, high gain antennae, radioisotope thermoelectric generators, heat shields, turbopumps, and propellant tank isogrids. You can imagine how long these lists can get.

"As applied to science fiction, it comes down to the flavor of the story being presented. A show might use a little or a lot of hard science and technology, and that can drive the look of something like a spaceship. Star Trek was all about spaceflight, so over the years all of the future technology was documented and worked into the ships and props. Other projects might want mostly a cool future style or a hint of plausible tech, but not everything would need to make sense."

What are you working on right now?

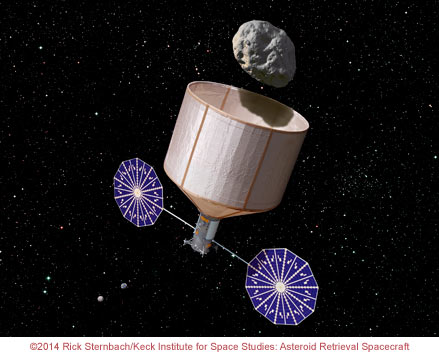

"To name two of my most recent projects — a model of an asteroid catcher for the Keck Institute for Space Studies, and a technical manual on the Klingon Bird-of-Prey for Haynes Publishing. Completely different kinds of clients, but both requiring a massive attention to detail."

Do you have any words of advice for artists who want to do what you do?

"If there’s one thing I would recommend over everything else, it would be to get a solid foundation in traditional studio art and art history courses. Learn to move a pencil or a stick of charcoal on a drawing pad. Take color theory. Look at Monet. Look at Ken Davies. Look at John Martin. Look at everything . Know what makes for good art before trying to make a computer display it. You’ll thank yourself."